The re-use of building parts is nothing new. Spolia, from the Latin for ‘spoils’, is the ancient custom of re-using stone or sculpture. For example, stone from Hadrian’s Wall was used in many local churches, and after the Great Fire stones from destroyed churches were reused in foundations and walls, notably in the crypt of the new St. Paul’s.

Historically it was also common to retain a building and provide it with a new façade, either to suit fashion, as with the 17th century rebuilding of Chatsworth House, or for essential maintenance as with Aston Webb’s Buckingham Palace façade of 1912. Our ancestors were entirely comfortable with the separation of a façade from its interior; see most Victorian railway stations and much of the work of John Nash. They recognised that buildings have two lives; one satisfying its internal programme, and another playing its part in the wider streetscape.

Façade retention, or to give it its academic name, facadism, is an inversion of this idea in which an existing façade is retained whilst the building behind is replaced. It’s a 20th century phenomenon which mirrors the general rise in awareness and influence of conservation. An early example is the Metropolitan Tabernacle at Elephant and Castle of 1861 whose front portico has been twice retained; once in 1957 following bomb damage and again in 1989 the result of a fire.

The protection of buildings of architectural or historical importance began in the late 19th century and became formalised in the Town and Country Planning Act of 1932. In 1967 conservation areas were introduced in response to concern over the pace of redevelopment and the recognition that townscape, beyond individual buildings, was also worth preserving. In practice, this added a layer of protection for unlisted buildings of merit but also opened the door to the concept of façade retention as a way of balancing context with development.

Despite several good examples, some unscrupulous developers have made a mockery of the approach over the years and shockingly bad examples are also only too common

Facadism hit its stride in the 1980s when technology made it more economically viable and the rise of the conservation movement increased pressure to preserve historic streetscapes. Despite several good examples from this era, such as Coutts Bank by Gibberd’s on the Strand, some unscrupulous developers have made a mockery of the approach over the years and shockingly bad examples are also only too common.

Facade retention is basically a temporary works solution, designed to maintain the building façade whilst the building behind is re-built. Setting aside the approach of dismantling and rebuilding stone-by-stone, there are three main types of retention:

- Scaffolding, suitable only for façades up to 4 storeys in height

- Proprietary props, ties and bracing suitable for taller facades

- Fabricated steelwork, used when the cost of hiring proprietary equipment over long periods of time outweighs the cost of fabrication

In central London type 3 is the most common and it can be either internal or external to the site. Internal restraint systems are best suited to tight urban sites where space is at a premium but they can pose a significant obstacle for contractors to work around. Whilst external restraint systems require more space, they free up the site interior for the new-build activities. They do however require separate scaffold for repair and decoration works.

MSMR is currently working on two retained façade projects in Westminster: Knightsbridge Gate for APML Estates and Morley House for the Crown Estate.

The latter is part of a series of exemplar façade retention schemes on Regent Street by the Crown Estate which demonstrate that commercial development can be undertaken whilst maintaining both a building’s principle heritage asset and the overall character of an area. It also illustrates many of the complications which can be experienced with façade retentions:

- Existing windows dictate wall positions, critical to residential developments, but also floor levels, which can limit development potential

- Its constrained site necessitates a mix of internal and external retention systems

- An on-site network sub-station is required to be maintained throughout

- Elements of deconstruction and reconstruction are required due to the building’s stepped form

- Acoustic isolation is required from the London Underground station below

Within the conservation community the approach still divides opinion: Historic England and the NPPF accept a hierarchy to a building’s significance, but SPAB rejects the reduction of buildings to mere façades.

This was evident, even in modern building, in the recent debate over parliament’s temporary home in the Grade II* listed Richmond House. Westminster’s own Supplementary Planning Guidance on Repairs and Alterations to Listed Buildings states, “Proposals for total demolition or demolition behind the façade of a listed building will not normally be acceptable”. However several notable projects have successfully justified the approach, for example 48 Leicester Square by Linseed Assets, or St James’s Market by The Crown Estate and Oxford Properties.

What facadism does offer is a pragmatic middle way between conservation and development

What facadism does offer is a pragmatic middle way between conservation and development. In reality few clients – and virtually no commercial clients – want a building that is “historic” through and through. When done correctly, retained facades can merge an heritage asset with a building that fits the demands of modern life. And whilst not fully meeting the demands of environmental campaigns such as the AJ’s RetroFirst, retaining a building’s façade should be more sustainable than building from scratch.

In Pictures: Two Facade Retention Projects

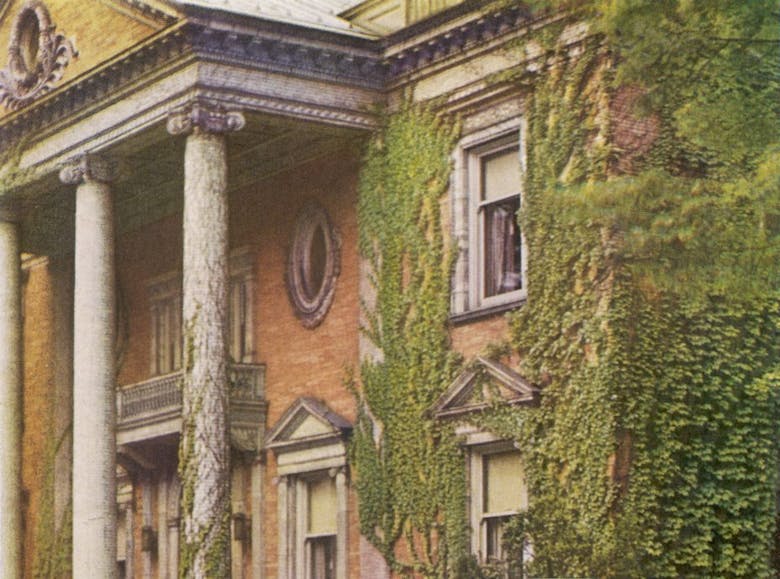

Knightsbridge Gate (Dixon Jones, MSMR, Richard Griffiths)

Morley House (MSMR)